In political science, the term “democratic transition” is used to describe a transition period in the history of a country that has recently gotten rid of a totalitarian regime and is “in transit” toward the formation of democratic institutions, that is a regime that is neither totalitarian nor yet democratic. There probably should be another term to describe the reverse process from half-established democracy to a dictatorship. This is the totalitarian transition we are witnessing in today’s Russia, and the authorities have not yet tightened screws enough to prevent the information about different aspects of this process from reaching the population. Thus, the much-publicized arrest of former leader of the Union of Right Forces opposition political party and Kirov Region governor Nikita Belykh brought to light a sensitive topic of “black cashboxes” controlled by government structures.

What exactly is a “black cashbox” of a Russian governor? First, it is worth noting that according to official estimates, 40 percent of monetary assets in Russia are circulating in the shadow sector of the economy. Unofficially, this number is much higher. According to Russia’s Central Bank, in 2015, the volume of cash in open circulation reached 400 billion rubles. It has to be said, however, that in 2014, it amounted to 1.8 trillion rubles. Russia is a recognized leader in illicit financial flows. A report released by Global Financial Integrity (GFI) examines Russia alongside India, Brazil, Mexico and Philippines. More than 40 percent of able-bodied population of Russia is employed in the shadow sector of the economy. During a 2013 conference at the Higher School of Economics, Deputy Prime Minister Olga Golodets declared that “it is unclear where” 36 million out of 86 million of able-bodied Russians “are employed, what they are busy with, and how”. In 2015, she stated that, as a result of the current crisis, the shadow sector of the country’s economy grew further by 5 percent.

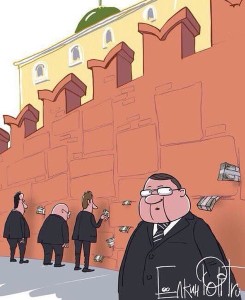

Practices that are considered barbaric in the West are quite common in Russia: envelope wages, all-cash real estate transactions, money stored in safe-deposit boxes. The Russian authorities also live by the laws of wild capitalism. State officials whose declarations of income feature, on average, anything from 2 to 5 million rubles a year own elite apartments and country houses the size and appearance of which make them look more like palaces, fly by private jets and spend their vacations on board ocean yachts. A widespread network of “black cashboxes” exists in the country alongside Russia’s official financial system. The results of the best known investigation of this problem were published by The New Times in 2007 in a piece entitled “Black Cashbox of the Kremlin”. Fearing criminal prosecution, Natalia Morar, author of this piece and reporter with The New Times, had to leave Russia. Even at the time, she wrote about duffel bags full of cash being brought in and carried out of state-owned banks under convoy of men in uniforms. These “common cash funds” have been used by the Kremlin to supply whom it deems necessary with unaccounted resources.

Everything is simpler on the regional level where there are fewer resources, ambitions are more modest, and the police and law enforcement bodies are less involved because of their federal status. In this context, pictures showing governor Belykh sitting at a table with piles of 100-euro bills totaling €150.000 laid out in front of him are hardly surprising. This was Russia’s reality ten years ago, and it is even more so today when, according to businessmen, they have to bring in money by suitcases – not envelopes anymore. The facts of the case are quite simple: the Novovyatski Ski Factory and the Forestry Management Company received 1.1 billion and 352 million rubles respectively from the budget of the Kirov Region for the implementation of priority projects. According to the investigation, this is what the governor was bribed for. This is actually a routine method of replenishing “black cashboxes”, and, as things go nowadays, €150.000 is hardly a large amount of money. Suffice it to remember Presidential Press Secretary Dmitri Peskov’s watch worth four times his annual salary; or Putin’s former bodyguard and current commander-in-chief of the National Guard Viktor Zolotov’ real estate worth 1 billion rubles while according to his declaration of income, his spouse and he together earn only 7 million rubles a year.

And one more reflection inspired by political science. A transition from a democracy toward a dictatorship is accompanied by a drastic strengthening of federal control over the functioning of gubernatorial “black cashboxes.” This is exactly what is currently happening. The turnover of illegally obtained money within different structures of the regime will be getting increasingly centralized in nature, and those opposed to the new rules will be severely punished. The discontent of regional elites will inevitably grow which will prompt Putin to increase repressions. The arrest of Belykh has marked the beginning of the Kremlin’s fight for survival in the context of decreasing revenues and in the absence of well-functioning governing bodies.

And one more reflection inspired by political science. A transition from a democracy toward a dictatorship is accompanied by a drastic strengthening of federal control over the functioning of gubernatorial “black cashboxes.” This is exactly what is currently happening. The turnover of illegally obtained money within different structures of the regime will be getting increasingly centralized in nature, and those opposed to the new rules will be severely punished. The discontent of regional elites will inevitably grow which will prompt Putin to increase repressions. The arrest of Belykh has marked the beginning of the Kremlin’s fight for survival in the context of decreasing revenues and in the absence of well-functioning governing bodies.