According to official data from the Russian Federal Statistics Service (Rosstat), Russia’s unemployment rate had been decreasing during the period from 2010 to 2014. Data from 2015 shows, however, that this trend has changed—the official unemployment rate demonstrated a minor but symptomatic increase of 0.5 percent and reached 5.8 percent. According to calculations of the Russian Ministry of Labor, in 2016, Russia’s unemployment rate could amount to 6 percent, and the situation is not expected to change significantly in 2017.

It is clear that in Russia official data concerning the population’s employment and unemployment rate can be considered only partially objective. The country’s shadow labor market where people are listed as either formally unemployed or employed for a minimal salary in one place while they are actually getting paid in cash somewhere else without declaring their income is just too big.

Rosstat claims that as of June 2016, the economically active population in Russia reached 76.9 million people (or 52 percent of the country’s overall population,) with 4.2 million of them being officially unemployed and another 30 million being employed in the shadow sector of the economy and not paying taxes, according to President Putin’s statement. In 2013, Deputy Prime Minister Olga Golodets declared that the “sectors that we can see and that are clear to us employ a total of 48 million. It is anyone’s guess where the others are employed, what they are busy with, and how”. Despite the president’s order to deal with this situation, it seems that no specific measures have yet been taken on the state level. Most likely, the government simply does not see any ways of remedying this situation, and the only thing left for Russian officials to do is to make mockingly sincere statements, like Medvedev’s most recent one about the paltry wages of teachers who can always find better jobs or make some money on the side.

In reality, teachers have no such option. According to the Russian Ministry of Labor and Social Protection, the average time spent on finding a new job is eight months, and today’s most wanted professions are the ones that do not require college degree. However, only a few years ago the situation was entirely different.

In 2015, the number of college graduates experiencing difficulties with finding a job has increased considerably, from 300.000 to more than one million. According to experts, there are five times more jobless people aged 15 to 24 years than unemployed people aged 30 to 49 years.

Meanwhile, the Western labor market is experiencing a rather successful period. For example, since the beginning of 2016, the U.S. has added 1.3 million new jobs and currently shows an unemployment rate of less than 5 percent. European data very. The rather wealthy Germany, where the unemployment rate has decreased to 6.1 percent, expects a further improvement due to general economic growth. The Czech Republic’s 4 percent unemployment rate is the lowest in Europe, and even Spain, Italy and Greece that traditionally have higher rates of unemployment do not spoil the overall European picture. Europe’s average unemployment rate stands at only 9 percent, which is the lowest in the last seven years.

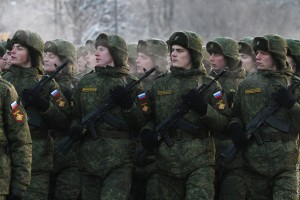

Employment and unemployment rates are excellent indicators of the state of the economy, and experts’ negative forecasts in this regard should at least make the Kremlin think about the necessity of reforms. On the other hand, when one listens to Medvedev, it becomes clear that, given the present political situation, no positive changes on the labor market should be expected. Furthermore, under Putin’s careful guidance, the country’s growing army, the recently established National Guard and the war in the Donbass that requires “volunteers”, provide the Russian population with employment. That way the regime is building up its armed support base of badly educated (since there are no teachers) but battle-ready “defenders of the Motherland” who are prepared to curb any Maidan-style protests inspired by the intelligentsia.