The Russian government approved the 2015 anti-crisis plan. Thus, authorities finally acknowledged the fact that the country has entered a crisis. However, according to the Russian media, it was recommended to the totally state controlled television to avoid using the word “crisis” itself. The new anti-crisis document represents a slightly modified version of the 2008 anti-crisis program. At the time, however, it was only thanks to oil price recovery that the country managed to get out of the crisis.

The Russian government approved the 2015 anti-crisis plan. Thus, authorities finally acknowledged the fact that the country has entered a crisis. However, according to the Russian media, it was recommended to the totally state controlled television to avoid using the word “crisis” itself. The new anti-crisis document represents a slightly modified version of the 2008 anti-crisis program. At the time, however, it was only thanks to oil price recovery that the country managed to get out of the crisis.

So what does the Russian government hope to achieve this time? The 36-page document can be narrowed down to a rather short list of ideas: additional capitalization of major banks, first of all state banks; the allocation of 188 billion rubles to finance the indexation of pensions (which will cover only a small part of the losses suffered by the population following devaluation of ruble);

allocation of funds to major companies; reduction of taxes for small-size businesses and the simplification of procedures for individual enterprises; restructuring of debts in foreign currencies and support for import substitution. The program will cost 2.3 trillion rubles. Simply put, the essence of the program consists in distributing money amongst those in need.

The program has a lot of drawbacks. First of all, new plan is not intended to address the causes but the consequences of the crisis. Furthermore, the plan does not even mention the necessity of structural reforms that economists have been talking about for the last twenty years. The country’s fundamental problems–a biased judicial system, corruption, and an ineffective state sector–are almost not covered at all. The Ukrainian conflict that puts a tremendous pressure on Russia’s economy and financial system is accepted as a given: the Russian government assumes that the current situation characterized by tensions and sanctions will remain the same at least until the end of 2017. In other words, the Russian government acknowledged that the country’s economy will have to be salvaged in the context of a long-term confrontation with the West. There is practically no hope that Moscow will revise its policy with regard to Ukraine.

Second, the pyramid of priorities is turned upside down. The fight against the ineffectiveness of state management that represents one of the most topical problems of Russian statehood and has a very negative impact on business is placed at the bottom of the list of anti-crisis measures. In fact, the solution of this problem is simply brought down to reducing particularly ineffective spending. Under Putin, however, this measure has never worked: in 2002-2003, Mikhail Kasyanov’s cabinet tried to make government bodies identify areas of ineffective spending on their own but the latter simply sabotaged the order. Furthermore, no real solution to the problem of downsizing the state sector has been offered: instead of selling state assets, the government proposes to continue bailing out state companies.

Second, the pyramid of priorities is turned upside down. The fight against the ineffectiveness of state management that represents one of the most topical problems of Russian statehood and has a very negative impact on business is placed at the bottom of the list of anti-crisis measures. In fact, the solution of this problem is simply brought down to reducing particularly ineffective spending. Under Putin, however, this measure has never worked: in 2002-2003, Mikhail Kasyanov’s cabinet tried to make government bodies identify areas of ineffective spending on their own but the latter simply sabotaged the order. Furthermore, no real solution to the problem of downsizing the state sector has been offered: instead of selling state assets, the government proposes to continue bailing out state companies.

Third, corruption–one of the most acute problems of the Russian economy–yet again turns out to be not a management strategy, but a “political project.” As a result, we witness managerial ambivalence: the cabinet issues an anti-crisis plan that lacks anti-corruption measures, while Kremlin Chief-of-Staff Sergei Ivanov makes a public statement on the subject of corruption using it as an instrument of promoting his bureaucratic and political rise. But even in this case the fight against corruption is, in fact, being substituted with a plan to “nationalize the elites.” This process started right after the beginning of Vladimir Putin’s third presidential term with the adoption of a law that banned state officials from having foreign bank accounts and keeping their financial resources abroad. The Kremlin’s disregard for the problem of corruption is understandable: the contract between the government and Putin’s elite, according to which loyalty can be exchanged for possible financial return, remains in effect.

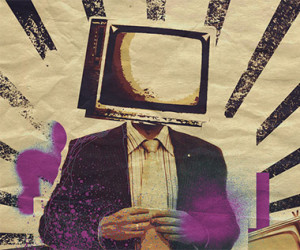

The main problem, however, is a social one. The new anti-crisis plan rescues large industrial players and banks, but does practically nothing for the country’s population. According to Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, if allocated funds are distributed among all pensioners, monthly pensions will rise by a mere 400 rubles. Russians do not get financial help, and they are deprived both of a political alternative and of the possibility to exercise their political rights (free elections ceased to exist on the federal and regional levels, and are on their way out on the local level). The new anti-crisis plan is based on the axiom of the population’s pathological loyalty to Putin. This idea is shared by the majority of Putin’s close circle, which means that the role of propaganda will increase drastically. This, indeed, seems to be the Kremlin’s real anti-crisis plan.