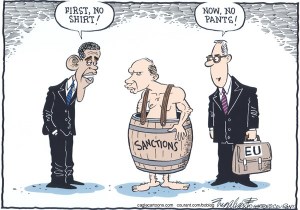

When in September 2014, Vladimir Putin imposed a food embargo on those Western countries that had introduced sanctions against Russia following its annexation of Crimea and the Malaysian Airlines Boeing crash over the Donbas sky, the Russian president’s decision did not cause much protest since it mostly affected consumers of imported products in Moscow and St. Petersburg and small and medium-sized businesses mainly involved in importing French and Finnish cheeses and American sport nutrition products. It is obvious that the Kremlin simply deems insignificant and thus ignores the interests of Russia’s middle class that includes private business owners and Russia’s urban intelligentsia. However, when the scope of import substitution reached the sphere of industrial technologies and propositions to substitute imported equipment used by major Russian enterprises started coming in, common sense — at least in the heads of those responsible for implementing such measures — sounded the alarm.

When in September 2014, Vladimir Putin imposed a food embargo on those Western countries that had introduced sanctions against Russia following its annexation of Crimea and the Malaysian Airlines Boeing crash over the Donbas sky, the Russian president’s decision did not cause much protest since it mostly affected consumers of imported products in Moscow and St. Petersburg and small and medium-sized businesses mainly involved in importing French and Finnish cheeses and American sport nutrition products. It is obvious that the Kremlin simply deems insignificant and thus ignores the interests of Russia’s middle class that includes private business owners and Russia’s urban intelligentsia. However, when the scope of import substitution reached the sphere of industrial technologies and propositions to substitute imported equipment used by major Russian enterprises started coming in, common sense — at least in the heads of those responsible for implementing such measures — sounded the alarm.

In today’s Russia, it is fashionable to be against all things American and European. It is no coincidence that Russians use derogatory words Gayrope and Pindos when referring to Europe and Americans to emphasize the decaying nature of Western civilization and its development impasse. People close to Putin understand very well that the current political trend is aimed at restoring Russia’s great power status and realize that the more patriotic their rhetoric is, the more affectionately the “national leader” will treat them. Thus, Russian top officials started talking about a wide-scale import substitution. Equipment manufacturers tried to lobby the government for preferential treatment. However, they faced a powerful opposition of major industrial enterprises urging against lowering quality in vital sectors.

While Russia’s Ministry of Industry and Trade (Minpromtorg) has been acting as the most active supporter of a wide-scale import substitution program, several industries and even a few government bodies have been simultaneously opposing this idea. For example, a heated conflict broke out in oil industry. The heads of Russia’s seven leading oil and gas companies (Rosneft, Lukoil, Gazprom Neft, Zarubezhneft, Bashneft, Surgutneftegas and Novatek) tried to defend their interests by sending a letter to President Vladimir Putin, in which they protested against a law introduced to the State Duma that provides for the tightening of control over equipment orders to encourage companies to purchase domestic equipment. Their argumentation is, however, rather interesting: according to them, the transparency of orders will suggest potential sanction targets to the West. Unofficially, the heads of aforementioned companies acknowledged that Russian made equipment cannot yet compete with imported one.

Another conflict broke out around electronics industry. When Minpromtorg approved an import substitution plan containing 534 articles (telecommunications equipment, computer machinery, electronic and optical components, software), the Ministry of Communications and Mass Media demanded that 65 types of equipment be eliminated from the list. Automobile manufacturers are not willing to switch to domestic equipment either. Healthcare Minister Veronika Skvortsova is categorically opposed to the proposition of Minpromtorg that is lobbying the interests of Rostekh and Almaz-Antei, to ban state purchases of imported medical equipment.

Another conflict broke out around electronics industry. When Minpromtorg approved an import substitution plan containing 534 articles (telecommunications equipment, computer machinery, electronic and optical components, software), the Ministry of Communications and Mass Media demanded that 65 types of equipment be eliminated from the list. Automobile manufacturers are not willing to switch to domestic equipment either. Healthcare Minister Veronika Skvortsova is categorically opposed to the proposition of Minpromtorg that is lobbying the interests of Rostekh and Almaz-Antei, to ban state purchases of imported medical equipment.

It seems that it is much easier to convince the population — or, rather, its small part — to give up imported gourmet foods than to force large industrial players to use domestic technologies and equipment the backwardness of which compared to their Western analogues is outrageous. Thus, the realization that market closures can never lead to economic development turn even the most ideologically fixated patriots into pragmatists. This might be the reason why the Russian elite has been showing signs of panicky agitation, and even the most notorious hawks with great-power ambitions have suddenly began calling for unification with Europe.