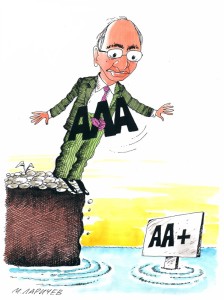

Russia is in the process of creating its own National Rating Agency that is intended to compete with the international “troika” of leaders: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch, whose ratings are recognized and used across the world. In the spring of 2014, all three international agencies downgraded Russia’s sovereign credit rating as well as the ratings of large state-owned companies, which the Kremlin considered to be a political and anti-Russian action.

Russia is in the process of creating its own National Rating Agency that is intended to compete with the international “troika” of leaders: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch, whose ratings are recognized and used across the world. In the spring of 2014, all three international agencies downgraded Russia’s sovereign credit rating as well as the ratings of large state-owned companies, which the Kremlin considered to be a political and anti-Russian action.

The decision to create a national (or sovereign, as it is sometimes called) rating agency in Russia was undoubtedly a political one. Valentina Matviyenko, speaker of the Federation Council, was the first to speak on this issue when she said that the country required agencies that would show an “objective picture” so as not to rely on rating agencies “biased by foreign governments.” Since March 2014, the establishment of a sovereign rating agency has been actively discussed at meetings held by First Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov. Even the supposedly liberal minister of economic development and trade, Aleksei Ulyukaev, has taken a hawkish position, denouncing ratings by the international “troika” as political and biased.

Today, there are nine rating agencies in Russia; three of them–Expert RA, Rus-Rating, and the National Rating Agency–are relatively large. Yet ultimately they are all medium-size consulting firms that are not known and, therefore, not trusted outside of Russia. Talk about creating of a “global” national agency that could compete with the big “troika” began during the 2008-2009 economic crisis, but did not go anywhere. In mid-2013, a new international rating agency, Universal Credit Rating Group, headquartered in Hong Kong, began operating. Alongside Chinese partners, Russia’s Rus-Rating played an active role in creation of the agency. Overall, no one outside Russia, and possibly China, was, until recently, interested in the services of these “independent” agencies, and the big international agencies continue to dominate the market, with their authority unchallenged.

When the Kremlin formulated the task that Russian agencies should replace, rather than complement, the international “troika,” patriotically oriented businessmen and their consultants rushed to implement the political command, anticipating big rewards. But they were confronted with a “technical” problem: how to create an agency that would be trusted, but that would at the same time have a “correct” (in the Kremlin’s view) understanding of national and geopolitical risks? For obvious reasons, it was decided not to create an “independent” agency wholly owned by the state, so its ownership was divided between 26 trusted investors: state-owned banks, insurance and investment companies, pension funds. It is already known, for instance, that the Kommersant publishing house, owned by Alisher Usmanov, will be one of these co-owners. The billionaire Usmanov is not only the husband of Irina Vinner, whose students include the gymnast Alina Kabaeva, a Kremlin favorite. He is also the owner of Russia’s largest metallurgical, coal, and media assets, who has bought Kommersant as a political favor to the Kremlin, to ensure that the nation’s largest business daily is not supporting the opposition. As for the head of the National Rating Agency, this position went to Ekaterina Trofimova, a top manager of the internationally sanctioned Gazprombank.

Twenty-six shareholders with equal stakes is a rather unusual ownership structure–especially for Russia, where companies usually have one majority shareholder. Such a structure was not chosen because of the Kremlin’s unexpected disposition toward civilized methods of corporate governance. The dilution of ownership stakes is intended to ensure the dominant role of the management, which will certainly be chosen in the Kremlin’s offices and will be overseen from the Central Bank and the FSB. Trofimova herself, it must be said, declared that a top-down management method will not work here. It is difficult to disagree with her, but Russian reality often conflicts with what is desired. Whatever the National Rating Agency’s managers say, its existence is especially relevant if international economic sanctions that have been imposed on Russia as a response to the annexation of Crimea and support for separatists in Ukraine, stay for the long term. And if, as seems likely, these sanctions remain in place for a long time, the economic indicators of Russian companies (and, with them, the sovereign and corporate ratings) will continue to decline, which will undoubtedly have an effect on the objectiveness of the self-assessment.